Beyond the Basics: Exclusive and Parallel Event-Based Gateways

19-02-2024

15 min

In the previous article, you learned the basics of Event-Based Gateways and how they allow Processes to pause and wait for decisions made by external Participants. Usually, these Gateways are in the middle of a Process, controlling which direction the workflow takes based on external Events.

But did you know there are two special types of Event-Based Gateways that can only be at the very start of a Process? These decide how the Process itself begins, not just how it branches in the middle. Understanding them helps you design flexible Processes that can start in multiple ways.

Standard Event-Based Gateway (in the middle)

Normally, an Event-Based Gateway sits in the middle of a Process. The Process is already running, and then it waits for an external Event before moving forward.

Notation: Diamond with double circles and pentagon

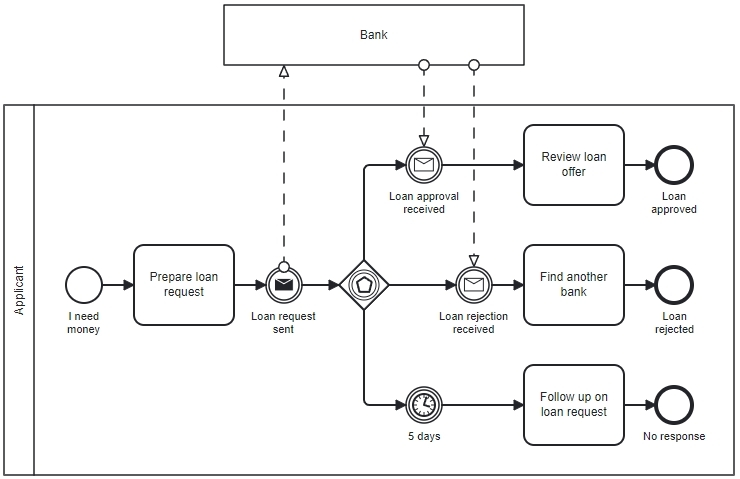

Example: A bank loan application

Example: A bank loan application

- Applicant submits a loan form.

- Bank validates the information.

- Now the Process waits.

A standard Event-Based Gateway waits in the middle of a running Process and chooses the next path based on whichever event arrives first. This creates a race condition:

→ The first Event that happens wins.

This type of Gateway is useful when the Process needs to pause and react to external responses - or even react to the lack of a response.

Examples of what might happen:

- If the bank approves the loan in 2 hours → approval path is chosen.

- If they reject it after 1 day → rejection path is chosen.

- If nobody responds for 5 days → timer path is chosen.

Two special Event-Based Gateways that start a Process

Event-Based Gateways can also be used to start Processes, but only in two special forms:

- Exclusive Event-Based Gateway (Start)

- Parallel Event-Based Gateway (Start)

Both appear only at the Process start and have no incoming Sequence Flows.

Exclusive Event-Based Gateway (Start)

Notation: Diamond with a single circle and pentagon

How It Works

- The Gateway listens for multiple possible triggering Events.

- The first Event that arrives creates a new Process Instance.

- Other Events are ignored for this instance.

This is perfect when the Process may begin in different ways, but only one starting path makes sense per case.

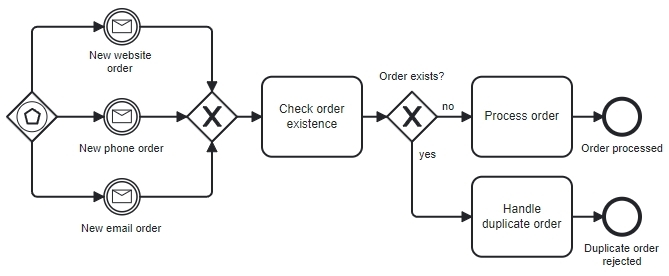

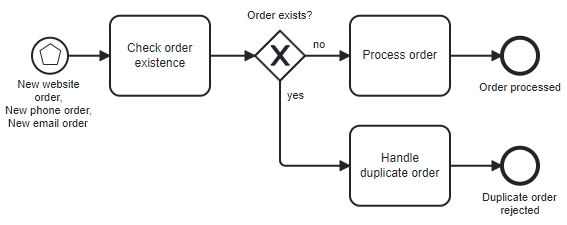

Example: Order handling using an Exclusive Event-Based Gateway to start a Process

Example: Order handling using an Exclusive Event-Based Gateway to start a Process

The order handling Process starts when a customer places an order.

Customers can place an order using three different channels:

- through the website,

- by phone, or

- by email.

Each order received through any channel starts a new Process Instance.

This means that if the same customer sends multiple orders through different channels (or the same channel), each order creates its own Process Instance.

To prevent processing the same order more than once, the Process includes an early check to determine whether the received order already exists in the system.

- If the order is identified as a duplicate, it is handled accordingly (for example, stopped or merged).

- If it is a new order, the Process continues.

In short: every incoming order starts a Process Instance, and duplicates are detected and handled inside the Process.

Alternatives to the Event-Based Gateway (Start) approach

While the above model complies with BPMN, there are simpler alternatives that can be used to start the Process without relying on an Event-Based Gateway.

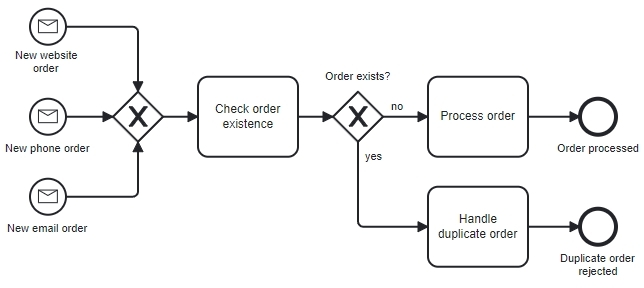

Alternative 1 - Multiple Start Events + XOR join (Recommended)

Example: Order processing using multiple Message Start Events + XOR join

Example: Order processing using multiple Message Start Events + XOR join

A much simpler and clearer alternative is to completely remove the Event-Based Exclusive Gateway and model each order channel as its own start event.

How it works:

- Use several Message Start Events: New website order, New phone order, New email order

- Connect all of them to a single Exclusive Gateway (XOR join)

Each incoming order message creates a new Process Instance, and the XOR join ensures that exactly one path is followed per Instance.

This alternative is:

- easier to read,

- easier to explain to business users,

- commonly supported by modeling tools,

- sufficient to forget about the Event-Based Gateway when starting a Process.

Alternative 2 – Single Multiple Start Event (Rarely Used)

Example: Order processing using a Multiple Start Event

Example: Order processing using a Multiple Start Event

Another alternative is to use one single Multiple Start Event.

How it works:

- Use a Multiple Start Event that reacts to: website orders, phone orders, email orders

- The Process then continues directly with checking order existence and order processing.

- No Gateway is needed at the start

Important notes:

- The Multiple Start Event is a rarely used BPMN Event type

- It is not commonly understood by business users

- It is not available or well supported in some BPMN modeling tools

For these reasons, this option is usually avoided in practice.

Final Recommendation

While all three approaches are BPMN-correct:

- The Event-Based Exclusive Gateway is often over-engineered for starting a Process

- The Multiple Start Events + XOR join approach is simple, readable, and widely supported

- The Multiple Start Event is technically elegant but impractical

➡️ The first alternative is good enough to completely forget about using an Event-Based Gateway to start a Process.

Parallel Event-Based Gateway (Start)

Notation: Diamond with a single circle and a plus (+)

How It Works

- The Gateway listens for several possible start Events.

- The first Event starts the Process, but - unlike the Exclusive Gateway - all remaining Events must still arrive eventually before the Process can complete.

- All Events must contain correlation data (e.g., Project ID) so they match the same instance.

This is useful when you need multiple inputs, but don't know in what order they will be delivered.

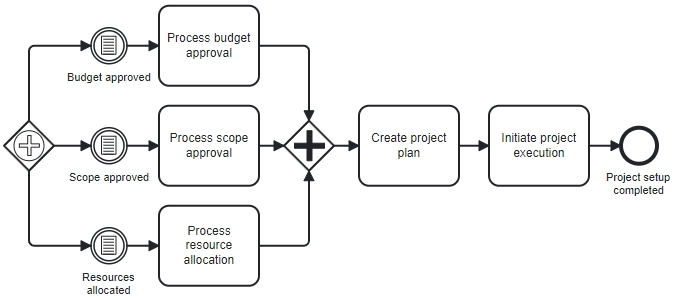

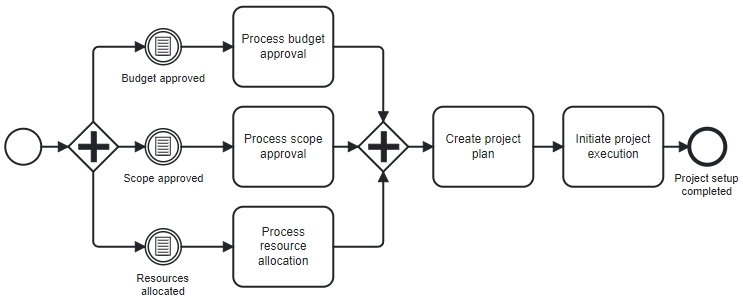

Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Event-Based Gateway

Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Event-Based Gateway

In the example, the Process can be triggered by any one of three approvals:

- Budget approved

- Scope approved

- Resources allocated

A Parallel Event-based Gateway at the start listens for all three Events at the same time.

Here’s what happens:

- The first approval that arrives starts the Process Instance

- The corresponding Task runs (for example, Process budget approval)

- The Process continues to wait for the other approvals

- Each approval is processed as it arrives

- A Parallel Gateway later synchronizes the flow

- Only after all three approvals are received the Process continues to: Create project plan and Initiate project execution

- The Process ends with Project setup completed

Any approval may arrive first and trigger early project setup - but the Process waits for all to complete.

A Natural Question

This works - but do we really need this fancy and rarely used Parallel Event-Based Gateway to model this behavior?

Can this example be drawn in a simpler and more common way?

Yes - and before showing those alternatives, it’s important to understand a common modeling mistake.

Why the diagram below is a bad example (Deadlock Risk)

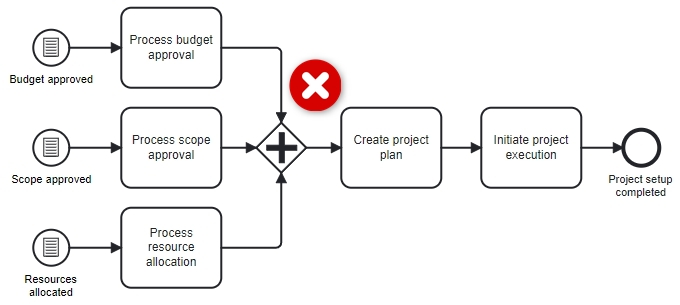

Incorrect Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Gateway that causes deadlock

Incorrect Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Gateway that causes deadlock

This is a bad BPMN model and often causes a deadlock. Why?

A Parallel Gateway used as a join requires all incoming sequence flows within the same process instance to arrive before it can continue. However, the incoming flows here originate from multiple Start Events, and Start Events do not synchronize - each one creates a separate process instance.

So what happens?

- One Start Event triggers and creates a Process Instance.

- That Instance reaches the joining Parallel Gateway with a single token.

- The Parallel Gateway waits for tokens from the other incoming flows in the same instance.

- The other Start Events create different Process Instances, so their tokens never arrive at this Gateway.

As a result, the Gateway waits forever and the Process Instance is blocked.

This is exactly why Parallel Event-Based Start behavior exists in BPMN - regular Parallel Gateways must never be used to join flows coming from multiple Start Events.

Because this Gateway is rarely used and not available in all modeling tools, people sometimes replace it with:

- A Parallel Multiple Start Event, or

- A None Start Event pattern where the Process starts normally, and later Events are handled using Intermediate Catching Events,

- or other (more complex) methods.

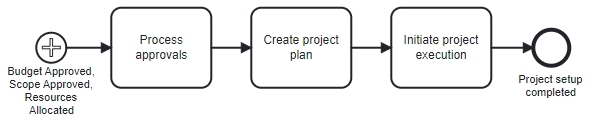

Alternative 1: Parallel Multiple Start Event (No Gateway)

Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Multiple Start Event

Example: Budget approval Process using a Parallel Multiple Start Event

Use:

- One Parallel Multiple Start Event

- Multiple triggers (for example: Budget Approved, Scope Approved, Resources Allocated)

Behavior

- The Process Instance is created only after all configured start triggers have occurred

- Each trigger is required

- The order in which the triggers occur does not matter

- No Process Activities begin until the last required trigger has been received

In other words, the start event represents a logical AND: the Process starts only when all approvals are available.

When this makes sense

- You want the Process to begin only after everything is approved

- Early or partial Processing is not needed

- The Process should always start in a “fully approved” state

Trade-Off

- You gain a very simple and compact model

- You lose the ability to start work as soon as the first approval arrives

Alternative 2: Single Start Event + Parallel Gateway + Intermediate Events

Example: Budget approval Process using two Parallel Gateways

Example: Budget approval Process using two Parallel Gateways

Another common pattern:

- One normal (None) Start Event

- Immediately followed by a Parallel Gateway

- Several Intermediate Catching Events

- Later synchronization with another Parallel Gateway

Behavior:

- Process is instantiated explicitly

- Approvals arrive asynchronously afterward

- Synchronization happens inside the Process

- This is often the simplest workaround which uses very common BPMN elements. It is easy for most BPMN tools and audiences.

Important note on these alternatives

The alternatives shown above are all valid BPMN modeling patterns and will work correctly, but they do not behave exactly the same as a Parallel Event-Based Gateway used at the start.

Each option defines a different moment at which the Process Instance is created and a slightly different relationship between Process start and incoming Events. Choosing one over another is therefore not just a modeling preference - it changes when the Process begins and how early work can start.

Summary Comparison

| Pattern | When Process is instantiated | When other Events occur | Semantics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Event-Based Gateway (Start) | First Event arrives | Remaining Events arrive later | Start early, wait for all |

| Parallel Multiple Start Event | Only after all triggers occur | Before instantiation | Start late, everything ready |

| Single Start + Parallel Gateway | Explicit start | After instantiation | Start explicitly, then wait |

Conclusion

Event-based Gateways allow BPMN Processes to react to external Events rather than internal decisions. Understanding the differences between their variants is essential for accurate modeling.

- The standard Event-Based Gateway (middle of Process) handles waiting and branching within an already running Process. It reacts to the first Event that occurs and cancels the others.

- The Exclusive Event-Based Gateway (start) allows a Process to begin in multiple alternative ways, with only one trigger determining the path for each Instance.

- The Parallel Event-Based Gateway (start) enables early Process instantiation while still requiring multiple related Events to arrive before the Process can continue.

While the start variants are powerful, they are also more complex. In practice, simpler patterns are often used, as long as the modeler understands how they change the semantics of Process instantiation.

The most important lesson is not which symbol you choose - but whether the model clearly expresses: when the Process starts, what Events it waits for, and how those Events are coordinated.